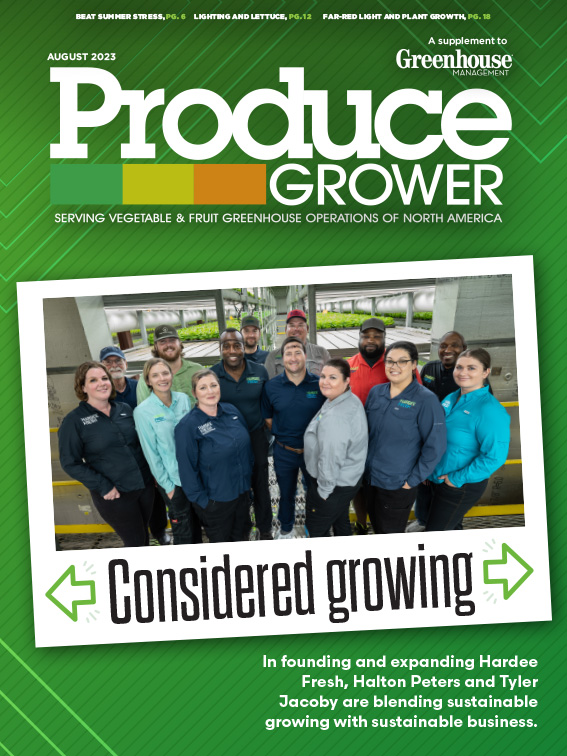

Hardee Fresh is expanding. But for the company to expand, it took years of careful growing and planning.

Founded in 2017 by Halton Peters and Tyler Jacoby, Hardee Fresh's base is in Hardee County, Florida. There, in a 54,000-square foot indoor farm off the highway, the company grows USDA-certified organic greens and herbs in a stacked system. The facility is also powered by solar energy and irrigation is done with their own well water that they reprocess. The idea, Peters and Jacoby say, is to make their take on indoor farming sustainable.

“In founding Hardee Fresh, we saw a number of trends,” Peters says. “There's demand from consumers for leafy greens and other vegetables that are more consistently safe, higher quality and available all year. There was also the trend of environmental challenges being faced by traditional producers in California and Arizona.”

Hardee County was also a specific choice. For one, there is labor in the county that has experience working in agriculture. Local leadership, Peters and Jacoby say, also sees Hardee Fresh as a forward-thinking evolution and are willing to collaborate.

Currently, Hardee Fresh is in the process of building two new farms. One, located near the original facility in Hardee County, will be a dedicated herbs facility. Another is a larger scale farm in Americas County, Georgia, that is on track to open in late 2024.

For the later facility, the company secured a $56 million bridge loan through X-Caliber Rural Capital. According to Jordan Blanchard, co-founder and executive manager at X-Caliber Rural Capital, the care and detail put into the Florida facility is what made Hardee Fresh someone they felt comfortable giving a loan to.

“One of the things is that they have an operating plant in Florida already,” Blanchard says. “In the world of USDA, we do a lot of startups, but going from conceptual to operating plant is riskier than conceptual to pilot plant to operating plant. Their facility in Florida is not really a pilot plant, but it's much smaller than the Georgia facility and allowed them to work out the kinks. That was a big selling point.”

“What we have seen over the last several years is that it's becoming increasingly difficult for West Coast producers to meet national demand because weather is not cooperating,” Peters says. “They are having a harder time meeting the demands for current customers, not even considering future heightened demand.”

The importance of education

The key to understanding Hardee Fresh is understanding the steps Peters and Jacoby took to get here.

Peters earned his bachelor's degree in biology from Stanford before earning a master's in plant sciences from the University of Cambridge, a Ph.D. in biology from Stanford and a Juris Doctor from Stanford Law School. Blachard, the X-Caliber executive manager, praises Peters “as one of the most educated people you'll find in all of anywhere, not even just CEA.”

After college, he worked in the energy space. That included working on incorporating renewable energy practices into data centers, airports and other kinds of facilities. That business is now done, but Peters says a lot of the thinking has been applied to Hardee Fresh.

“Halton is extremely creative and conscious about how he spends our money,” Jacoby says. “We don't spend unless we know it's going to give us more efficiency.”Jacoby, meanwhile, grew up around the golf course management industry before getting a bachelor's degree in horticultural sciences from Florida Southern College and then his master's degree and Ph.D. from the University of Florida. In college, Jacoby says he was exposed to “every kind of growing you could think of.” Peters calls him “one of the leading young agronomists in the country.”

After earning his Ph.D., he went to work as an agronomist at a startup company. There, he was tasked on the first day to build an agriculture lab that could analyze pest and disease issues for outdoor berry growers in Florida.

Peters and Jacoby met around this time. Peters told Jacoby about the work he was doing on lighting and approached Jacoby about his interest in collaborating on a vertical farming project. In 2017, they founded Hardee Fresh. Their first hire was Clint Honeycutt, Jacoby's roommate at Florida Southern and the current general manager.

“Halton and I spent about a year, year and a half designing the farm,” Jacoby says. “We then brought in Clint with his expertise and he tweaked a lot of things and we redesigned some things and made it more efficient.”

“Indoor farming is a confluence of a lot of the themes of what I’ve and we’ve been working on for a long time,” Peters says. “That’s in our novel approach to agronomy or how we incorporate energy efficiency to the way we incorporate micro elements into the farm.”Organic, Peters says, also an intentional choice. He and Jacoby’s research into the market led them to think that organic was something customers were demanding.

“Everything we do at Hardee Fresh is about what customers demand,” Peters says. “Customers want something clean and safe. And they want the same thing week after week after week.”

Why now for growth

Right now, Hardee Fresh products are sold in 13 different states, mostly through Whole Foods. As they add more growing capacity, they expect to reach new states and retailers. Their product is sold through their own label, but also under private grocery labels.

“Our goal as an indoor farming company is not to be in downtown Miami or nestled next to a high-density population in New York City,” Peters says. “Rather, our strategy is to be close to the local distribution hubs where leafy greens are picked up. Our country has a network for the translation for perishable goods, so we want to take note of that existing infrastructure and take advantage of those distribution hubs that serve consumers rather than consumers themselves.”

The second Hardee County facility and the farm in Americus are different kinds of builds. The former, fully dedicated to herb growth, is going through a retrofit where a hospital is being turned into a farm.

“All of our retail partners, or any potential partners, want herbs,” Jacoby says. “So to get into new places, you have to give them herbs.”

The former is a brand-new build that is a scaled-up version of the original facility. When completed, it will be roughly 340,000 square feet and feature more automation than the original facility. The Americus facility also will be able to pre-package processed salads for customers; Jacoby says that's a “huge opportunity” for the company.

Both, though, are the product of careful planning. The Americus project has been in development since 2019, but was taken slowly to be done correctly. It also let the company mature to a point where it had demand from retail customers that their current setup couldn't keep up with.

“We are about the long-term play here,” Jacoby says. “Halton and Clint and everyone on our time take this seriously, especially the growing part.”

“We want to be thoughtful about how we expand,” Peters says. “Thoughtful geographically in terms of our relationship to the community and a community we want to be a part in building.”

Explore the August 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- DENSO and Certhon introduce Artemy, a fully automated cherry truss tomato harvesting robot

- Landmark Plastic celebrates 40 years

- CropLife applauds introduction of Miscellaneous Tariff Bill

- UF/IFAS researchers work to make beer hops a Florida crop

- Nature's Miracle announces initial shipments of "MiracleTainer" series container farm

- Local Bounti opens new high-tech controlled environment agriculture facility in Pasco, Washington

- NatureSweet responds after ruling by U.S. Court of International Trade that invalidates tax on tomato imports from Mexico

- Former Danone executive becomes chief operating officer at NatureSweet